“It may peradventure be thought, there was never such a time, nor condition of warre as this; and I believe it was never generally so, over all the world: but there are many places, where they live so now. For the savage people in many places of America, except the government of small Families, the concord whereof dependeth on natural lust, have no government at all; and live this day in that brutish manner, as I said before. Howsoever, it may be perceived what manner of life there would be, where there were no common Power to feare; by the manner of life, which men that have formerly lived under a peaceful government, use to degenerate into, in a civill Warre.”

—Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan. 1651.

“Thus in the Beginning all the World was America, and more so than that is now.”

—John Locke, Second Treatise of Government. 1689.

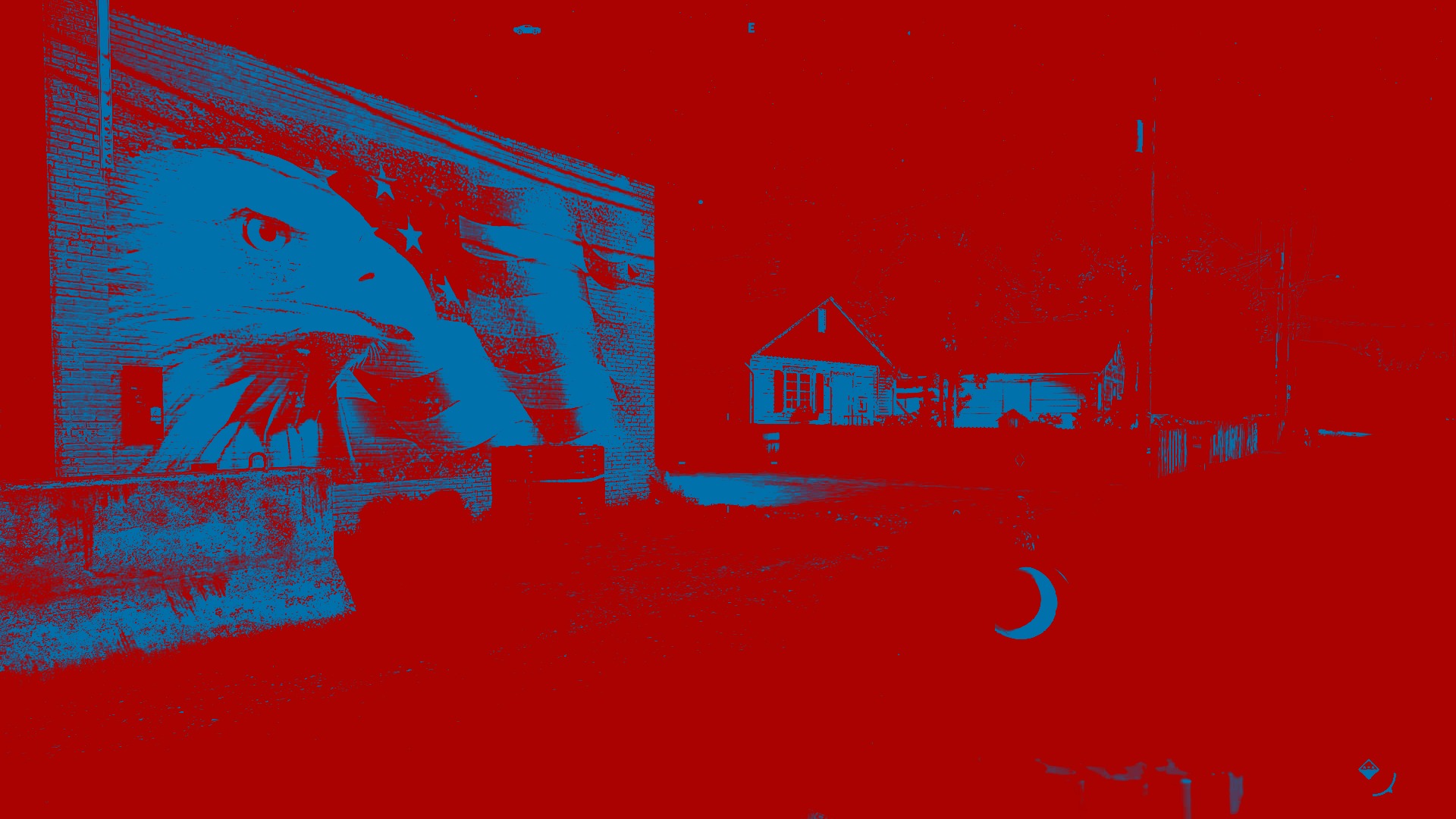

There was a tremendous opportunity in the decision to shift Far Cry 5’s setting from the self-consciously “exotic” locales of Far Cry 3 and Far Cry 4 to the rural American West. If there is a thesis buried under the firearm fetishism of the Far Cry games, it is that violence is the only functional source of authority, legitimate or otherwise, and no government is in the end capable of raising humanity above its drive for power at any cost. The only possible source of virtue, therefore, is in the properly directed exertion of violence—the lone individual destroying those who would threaten their life or property, and who extends a sphere of protection to those who support their authority and autonomy within that sphere.

This is, of course, the fantasy of the American frontier, and as expressed in the quotes above, this myth predates the creation of the United States by at least a century. While John Locke in particular serves as the foundation for the late-Enlightenment liberal democratic (small-l, small-d) political philosophy on which the United States was constructed, Thomas Hobbes’ more pessimistic conception of the ungoverned human condition informs a great deal of storytelling centered on the limits and boundaries of the reach of the State. This includes not only the Far Cry games, but also Apocalypse Now, post-apocalyptic stories like Mad Max and The Walking Dead, and the entire tradition of the American Western.

There is no government in Far Cry 5. The sole federal employee among the cast, a US Marshall who leads an ill-considered and understaffed raid on the headquarters of the apocalyptic Project at Eden’s Gate cult that initiates the game, is by the end of the story dead by his own hand. The only representatives of local authority are the County Sheriff and three deputies (including the unnamed player) each of whom (including the player) is captured and held by one of Eden’s Gate’s villainous Seed siblings at some point. With the exception of the prison fortified by Sheriff Whitehorse after the failed raid (described as being abandoned before the events of Far Cry 5), there is little evidence of government presence, federal or local. Even the Hope County Sheriff, it would seem, is based outside of Hope County.

This, again, is the fantasy of the frontier—open country beyond the reach of the traditional state. The irony of this fantasy, of course, is that the federal government arguably has more direct involvement in many rural areas than it does in most urbanized areas. There is a reason why the Bundy family in Nevada—where nearly 85% of the state’s land is owned and administered by the federal government—chose a National Wildlife Refuge as the site of their armed occupation. (And why local citizens and authorities in Oregon, where the refuge was located, did not necessarily welcome that occupation.)

But perhaps the more cogent irony is that while there is no government in Far Cry 5—no one the player can call on for help, and thus no functional, legitimate source of the deputy’s authority—it is absolutely incorrect to say that Far Cry 5 is ungoverned. As a videogame, Far Cry 5 is ultimately a set of systems in which the player is free only insofar as that freedom has been directly envisioned and accommodated by its systems. This is most obvious on nine occasions where a member of the Seed family captures the deputy in order to make the player sit through a narrative cutscene. But it is no less true in that if the player chooses to ignore story missions and go fishing that she can do so only because the game has created lakes and rivers, stocked them with virtual fish, and given the player a fly rod to use to catch those fish. Her “freedom” exists within the confines of the game’s design. This is, indeed, a level of constraint beyond even Hobbes, in which the liberty of the subject exists “where the Soveraign [sic] has proposed no rule.” In Hobbes, if the king doesn't care about butterfly collecting, I'm free to do it. In Far Cry, I can't collect butterflies because no one created them, no one gave me a net, and no one created a set of conditions for the two to interact.

Far Cry 5, of course, is not unique in this level of constraint. As a game (and not just as a videogame), it must be at least in part a set of rules. If it is designed well, these constraints are generally pleasurable, and while Far Cry 5 is not the most well-designed set of systems I have ever played (and it is not even the most well-designed set of systems I have ever played as a Far Cry game), the pleasures and failures of pleasure in Far Cry 5 don’t strike me as being particularly outside the norms of a contemporary blockbuster videogame.

In fact, if it is not already apparent, I am having some trouble actually talking about Far Cry 5 itself in writing about Far Cry 5. The fantasy of Far Cry 5— that a series premised on the license to commit righteous violence in the context of the breakdown (or absence) of the state in an exotic location might by shifting its setting to the United States offer the possibility of examining what that license looks like when the object of that violence isn’t an exoticized Other, or maybe even a cogent satire of the dominionist strains in American theology—is far more interesting than the flat, consciously insubstantial reality of Far Cry 5. What ultimately can I draw from an experience in which I have, at the time of this writing, killed without much thought 2,304 digital “people,” only five of whom were even lightly sketched out as anything resembling characters? (This number of kills, incidentally, is greater than the 2017 populations of thirteen of Montana’s 56 counties. With another few hours of play I’m sure I could push that number past Liberty County’s 2,427.)

The fantasy at play in the reality of Far Cry 5 is in fact no different than any of the other Far Cry games (at least since Far Cry 3), or, at their core, any other open-world shooter: the fantasy of anarchy within a system that insulates the player from any significant possibility of functional anarchy or the consequences of the violence that such anarchy is presupposed to necessitate and justify. While player “death” may be frequent, the only possible negative outcome is a momentary failure to acquire more power or progress in the narrative. This insulation is in fact so deep an assumption of design and play that we treat the handful of games that decline to offer it as either visionary experiences or deep failures of product design—either brilliant or “unfair” and “broken.”

And what can such a fantasy possibly have to say about anything real?

While John Locke and Thomas Hobbes each share the idea that the natural state of humankind is one of individual, ungoverned liberty, they differ as to whether the conflicts that arise from such a condition are essential or incidental. In Locke, the State of Nature (a state of perfect freedom and equality between individuals, in which none has authority over any other) is distinct from the State of War, which arises when one man seeks to exert binding authority over another. (I use “man” rather than “individual” or “person” when talking about Hobbes and Locke because Hobbes and Locke were thinking about men rather than people.) In Hobbes, on the other hand, the State of Nature is necessarily a condition of war “where every man is Enemy to every man,” and “the life of man [is] solitary, poore [sic], nasty, brutish, and short.”

In Locke, society exits the State of Nature when men come together and exchange their natural state of total liberty for a mutually constituted system of laws. These are agreed upon for their protection and prosperity, to “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to [themselves] and [their] Posterity.” In Hobbes, on the other hand, the only path out of the State of Nature is the creation of a despot who in effect protects men from the arbitrary exertion of absolute authority by becoming the embodiment of absolute authority. (That is, men protect themselves from other men by creating a single man from whom there can be no protection, one despot rather than a multitude of thieves and murderers. This is as good as it gets in Hobbes.)

It is important to observe that in both Locke and Hobbes, the State of Nature is a fantasy, but they are different fantasies with different outcomes, and if Locke’s fantasy helped shaped the aspirations around which America built its imperfect social and legal systems, it is Hobbes whose fantasies haunt the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and who we wish we had the license to be. When Far Cry resolves in a condition where no authority is legitimate because not only is it impossible for the Social Contract to endure, it is impossible for individuals to enter such an agreement in good faith, it is Hobbes’ voice we hear, muddled, debased, but still recognizable. It doesn’t really matter if such ideas have any basis in reality—whether even in the condition of war real people still tend to seek community, even when the only communities available are communities of war. It doesn’t matter that the America both Locke and Hobbes imagined never existed, that the people they imagined as “savages” lived in societies every bit as real, legitimate and mutually constituted as the still-not-yet-modern states of 17th century Europe. The fantasy of the State of Nature in both Far Cry and Hobbes is absolute license, the individual as despot. This is the fantasy of the frontier: the lone individual of virtue as the only and absolute authority, accountable to no one and beyond the reach or even the possibility of the state. The citizens of Hope County may call the player “Deputy,” but what they really mean is Leviathan.

***

Gavin Craig is a writer and critic who lives outside of Washington, D.C. Follow him on Twitter @craigav.